Author Amit Majmudar

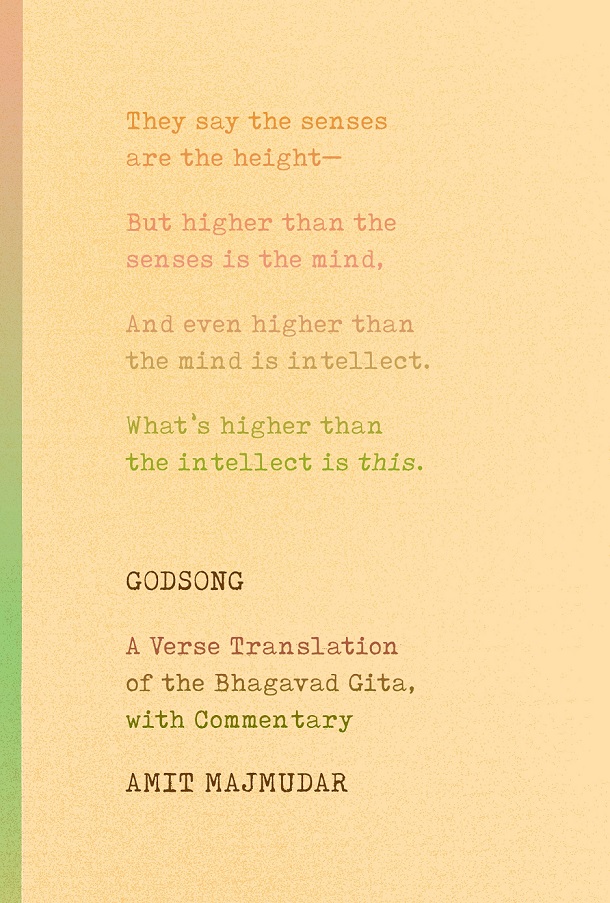

The Bhagavad Gita, the sixth book of the Hindu epic The Mahabharata, has been translated into over 75 languages, and in English alone has 300 published translations. This book, often considered the Hindu equivalent to the Christian bible, has been cherished by not only prominent spiritual figures, but also authors such as Aldous Huxley, Henry David Thoreau and Herman Hesse; political figures such as Gandhi and Steve Bannon; and scientists such as J. Robert Oppenheimer, who famously quoted after the first nuclear test "Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds." Have I convinced you that it is a big deal? It would be easy to say that the work on this book has been done. It would also be easy to feel that tackling this work should be left to the experts. But then again, the book itself would unravel those statements, emphasizing that our “dharma” should be done, no matter how difficult the task at hand. Amit Majmudar, a radiologist and writer from Ohio felt that it was his dharma to give this ancient text new life in a translation he calls Godsong.

Majmudar, the son of Indian immigrants, had been familiar with the Bhagavad Gita since childhood. As he approached his teen years he realized as many of us do, that he wanted to know the truth. In a world where science and religion are constantly at odds, he says, “Mathematical beauty was universally, absolutely, literally true.

Religious beauty was true too, but only in a private, almost figurative sense.” If religion then is a personal truth, there are “as many truths, as many ideas of the divine, as there are human beings.” For Majmudar, the Bhagavad Gita is his truth, making this project one of dharma, but also bhakti or devotion.

Often referred to as simply “The Gita,” this text is thought to have been composed between 400 B.C and 200 A.D by Vyasa, one of seven “Chiranjivans” or immortals. It is 700 verses that tell the story of the hero warrior Arjuna who finds himself on a battlefield positioned to fight his own friends and relatives. Looking for advice he turns to his charioteer, who happens to be God incarnate Krishna. How is he to embark on this battle against his loved ones? And so the story begins. The text’s aim is to give visibility to the true nature of God and acts as a “how-to” guide to discovering the cosmic secret.

Majmudar says in the preface, “The first task of translation is finding a way to sound as little like a translation as possible while still maintaining accuracy.” Godsong is both graceful and accurate. The lines have fluidity and rhythm traditional translations sometimes lack, while maintaining the core teachings the text aims at communicating. Majmudar is able to capture the essence of this text’s ancient roots through the language choices, using terms that are both poetic and direct. But Majmudar does not leave out a sense of modernity. For example, in Session 2, Verse 2 Krishna responds to Arjuna’s resistance to fighting in the battle.

The Blessed Lord said,

Where’s this gutlessness coming from?

In a time of danger!

This is goddamned unbecoming.

This disgraces you, Arjuna!

Compared to a more classic translation, the 1973 version by Swami Prabhupada that has been handed out in the streets of every major city by the Hare Krishna movement, Chapter 2, Verse 2 states:

The Supreme Personality of Godhead said: My dear Arjuna, how have these impurities come upon you? They are not al all befitting a man who knows the value of life. They lead not to higher planets but to infamy.

“Gutless” verses simply “having impurities” will certainly have more of an impact in our culture. In the same way, “Goddamned unbecoming” has a more contemporary sense of understanding than simply “befitting.” It is as if Arjuna is runway bound in last year’s dress, rather than one simply a little too short.

In terms of approach, Majmudar takes a traditional one, maintaining the verse format and even some of the Sanskrit language. After the introduction, Majmudar does his due diligence to ensure the readers will understand the terms he left alone. In “A note on the words I didn’t translate,” he says these words “express concepts absent from the Western tradition, and hence from English itself.” A few of the words he leaves, dharma, maya and yoga. He says, “While I am aware that the word yoga conjures, for most Americans, urban thirty-somethings in yoga pants on yoga mats deep-breathing and relieving stress, I had to keep this word as is. Commoditized, physical, studio-yoga has little to do with the Gita.” Amen.

I appreciate Majmudar’s directness around this bastardization of “yoga”

in our culture. At the same time, though, I think he is making a real attempt to create a translation that is accessible to even the Lululemons crowd. “The Gita imagined a relationship in which the soul and God are equals. It’s a relationship mostly missing from every other scripture: friendship.” This friendship and equality is demonstrated in the way Arjuna and Krishna communicate, as in Session 18 verses 63-64:

I’ve explained to you a knowledge

More secret than the Secret.

Mull this over, the whole of it.

Do what you want to do…

Hear me out again. My highest word,

The secret of all secrets:

I love you. Hard. That’s why

I speak, to do you good.

First of all, the idea of God inviting one to “do what you want to do” without immediate consequence is certainly friendlier than most Christ-based religions offer. In addition, “I love you. Hard.” has a certain millennial-bro ring to it that makes me believe God is on my team. Yay, God!

Beyond the translation, Majmudar offers commentary that is almost as beneficial as the text itself. The “Listener’s Guide,” as he calls it, not only provides context on his own process, but it also adds a dimension of understanding to the Gita and the Hindu landscape in which it was created. Most importantly, he addresses the caste system, something uniquely Indian and also controversial.

It would be impossible to write a modern translation of the Gita without addresses this provocative subject. In the Gita, God states directly that He is the creator of this system as for example, in Prabhupada’s translation, Chapter 4 Verse 13: According to the three modes of material nature and the work associated with them, the four divisions of human society are created by Me. And although I am the creator of this system, you should know that I am yet the nondoer, being unchangeable.

Majmudar takes a similar approach to the verse:

I created four castes that

Apportion works and gunas.

Though I am their maker,

Be aware I do not do things.

In the listener’s guide Majmudar first clears up the misnomer/misunderstanding that all Hindus are a part of the caste system and it is essential to the religion. He says, “hundreds of thousands of Hindu Americans (and Hindu Indians) like me, are living examples of that [caste system].” The parenthesis reminds me that he is writing this translation for the West and possibly for the Westerner who does not already consider themselves a Hindu. He goes on to remind us that all cultures and all religions struggle with equality. He proposes that, “The Gita explains both our differences and our sameness. It acknowledges the different classes of people ant the different work they do in the world, but it asserts their underlying metaphysical sameness.”

Sameness. Friendship. Love. Suddenly this ancient text is sounds like a Beatles song. Have we all stopped listening? Ah, but the Gita also keeps us in check with real life. Life is a battlefield isn’t it? Amit Majmudar succeeds in offering a translation of the Bhagavad Gita that can be appreciated for its ancient spiritual teachings and also accessed in the real-life modern world. I hope Yogis and non-yogis alike will take the time to see it for what it is. In the last lines of Majmudar’s translation:

Wherever Krishna Lord of yoga is,

Wherever Arjuna the archer is,

There must be splendor, triumph, wealth,

And ethics. This is my belief.

Somehow the ending lends itself perfectly to Majmudar’s mission, and his landing belief that “we are each other” and the Gita “is my truth.”

Aditi Muir is East West Bookshop's operations manager. She can often be found meditating, reading, writing or hiking. She is a full time graduate student at Naropa University's Jack Kerouac School for Creative Writing. She is currently working on a book of poems and lyric essays that she hopes to find a publisher for this spring. (Fingers crossed.) She is also a certified Yoga Instructor in Hatha and Restorative. She has taught in Hawaii and San Francisco and hopes to eventually teach more classes here in Seattle. For the last decade she has worked as a District Manager for a Corporate Retailer and though it was a fun experience that took her around the world, she feels privileged to be working at East West and serving this community.