The summer before my final year of graduate school, my classmates and I went on a ten-day wilderness retreat high in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado. The central purpose of this retreat was to prepare for and take a three-day backcountry solo. On our own, we were to each find a spot in the wilderness where we were to stay without food or shelter for three days and three nights.

Before I left on my solo, I worried that the lack of food might interfere with my decision-making. I worried that I might have a panic attack or get sick. Conversely, I imagined that the experience could be relaxing, that I might even feel bored. In reality, once I was alone in the wilderness I did not feel bored or have a panic attack. I felt pretty sure I was going die from a bear or mountain lion attack. I had no house or tent; no weapons, no fire; I had nothing to protect myself. I was totally unprepared for how scared and vulnerable I felt in the wild. I was amazed by how quickly all concerns of my former life disappeared as my focus honed in on survival. How could I save myself?

In that new and vulnerable place, I found myself turning instinctively and entirely to ritual.

I followed the sun or shade around the small meadow I had chosen for my three-day stay (a meadow, I was now certain, that bears would come from long distances to eat the small blueberry bushes along its perimeter). I set up small altars with flowers and items I’d found. I prayed and meditated, sang and danced. And each night as I lay down under the stars, I would acknowledge that this night I might die; I might wake to a bear’s giant face and that would be the end of me.

At the end of the three days, back in warmth and safety, I marveled at what a creature of ritual I had become during those days. What had ritual offered me in my fright and uncertainty? And what did ritual have to offer me in my life away from the bear meadow? During the holiday season, I find it particularly helpful to revisit these questions.

In our daily lives, it is easy to feel insulated or distant from death. For most of us, there is hardly ever an opportunity to feel utterly defenseless in the face of, for instance, a wild animal attack. Yet all the same, underneath all the layers of busyness in our lives, we know that time is passing. We know that we are getting older; that life will unfold before us and before those we love in ways we cannot possibly anticipate or control. Whether we pay attention or not, the sun is rising and setting, the seasons are moving slowly through their great circle. Rituals—daily, weekly, or yearly—can allow us to pay attention to our place in the great, ever-changing mandala of life.

At the end of the three days, back in warmth and safety, I marveled at what a creature of ritual I had become during those days. What had ritual offered me in my fright and uncertainty? And what did ritual have to offer me in my life away from the bear meadow? During the holiday season, I find it particularly helpful to revisit these questions.

In our daily lives, it is easy to feel insulated or distant from death. For most of us, there is hardly ever an opportunity to feel utterly defenseless in the face of, for instance, a wild animal attack. Yet all the same, underneath all the layers of busyness in our lives, we know that time is passing. We know that we are getting older; that life will unfold before us and before those we love in ways we cannot possibly anticipate or control. Whether we pay attention or not, the sun is rising and setting, the seasons are moving slowly through their great circle. Rituals—daily, weekly, or yearly—can allow us to pay attention to our place in the great, ever-changing mandala of life.

When I became a mother, I discovered that ritual quickly became vital. While my children were very small, you would probably have heard my husband describe this love of routines and ritual as “impossibly tied to a strict schedule,” but in the face of keeping another human being alive, my rituals became lifelines. Now, as the mother of growing children, my rituals are simple and based on ideas in the Cayce readings—allowing for imaginative play, lots of time outside, and stories.

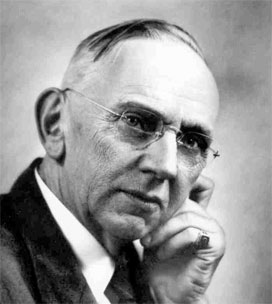

The readings encourage parents to establish routines with their children. In several readings Cayce noted that when a child is in a healthy rhythm, weaknesses can be corrected. Routines can build constructive actions that become natural and habitual and lead to helpful thoughts and wise decisions.

One that will ever be found to be inclined to be neglectful at times. This may never be corrected by scolding, but by giving routine work, or routine formulas, that may bring coordinated unison of its thinking. (3204-1)

Tiny rituals nurture children and their sense of place in this great world, just as bigger, grander rituals do. My four-year-old recently asked about circles. Each day creates a circle as the sun moves across the sky. And just so for our family—from morning cuddling, to talking about dreams en route to school, to afternoon story time while swinging on the swings, to snack and garden weeding, to sweeping after dinner—these dependable rhythms ground us and help us feel the circle of our day. Some days are rushed with new activities, or we are traveling, or have visitors, each of which brings its own excitement and specialness. But when we are in our usual daily rhythm, sometimes I notice a sacred relationship to time. It is then that I realize anew how our simple routines are in fact deeply grounding. I define and describe time in terms of these rituals. Our rituals are an offering that celebrates what is meaningful to us. I am reminded that I want to choose these rituals, to create our family rhythm, skillfully and with intention.

In our home, more defined and exciting rituals are shaped by our children’s Waldorf schools and by their founder Rudolph Steiner’s fundamental belief in human beings’ natural attraction to and appreciation of rhythm. He wrote in Signs and Symbols for the Christmas Ritual, “Rhythm holds sway in the whole of nature, up to the level of man. Then, and only then is there a change. The rhythm which through the course of the year holds sway in the forces of growth, of propagation and so forth, ceases when we come to man. For man is to have his roots in freedom; and the more civilized he is, the more does this rhythm decline. As the light disappears at Christmas time, so has rhythm apparently departed from the life of man. Chaos prevails. But man must give birth again to rhythm out of his innermost being, his own initiative.”

Steiner’s Waldorf schools mark the change of seasons and holidays with festivals. Parents, teachers, and children come together for simple performances by the children, stories, music, and snacks. As these festivals and simple birthday celebrations have become part of our family life, I can see how they help my children—as well as my husband and me—to adjust to change. They help us to let go of current seasons and the way things are right now, and welcome what comes next, to feel safe in the face of the reality of constant change and uncertainty.

With the traditional rituals—Thanksgiving, Christmas, Easter, birthdays—much of the rhythm and ritual is in the preparation, so I try to remember to leave ample time to enjoy it. In advance of a celebration, we begin singing songs for that particular celebration, gathering items from nature that are available during that time of year, baking special foods, telling the stories we know so well. I try to look for that moment when all the preparation and hard work pays off, to remember to feel that moment of stillness when it all comes together. At a birthday, it is usually when we sing. I hear the voices of those who love my child and are watching her grow. I see that her shining face is a sparkling reflection of the bright star she is in our life. And I think, “Oh yes, I remember now: we are here to love. We are here to enjoy this time together.” Rituals offer us these vital glimpses into how the moments of our lives are grand pieces in a larger tapestry.

Joseph Campbell, who could well be the greatest authority on mythology and its place in contemporary culture, writes in Thou Art That, “another function of traditional mythology is to carry the individual through the various stages and crises of life—that is, to help persons grasp the unfolding of life with integrity. This wholeness means that individuals will experience significant events, from birth through midlife to death, as in accord with, first, themselves, and secondly, with their culture, as well as, thirdly, the universe, and, lastly, with that mysterium tremendum beyond themselves and all things.” This insight into one of the roles of mythology—of which ritual is a part—helps me better understand why I turned to ritual in the wilderness, why it is so central to my mothering, and why I am happiest when held in the circles of our family rhythm.

For the home is the nearest pattern in earth…to man’s relationship to his Maker. For it is ever creative in purpose from personalities and individualities coordinated for a cause, an ideal. (3577-1)

Making pancakes in the early morning light, returning to the same prayer before sleep each night, picking azaleas and lilac for birthday bouquets each spring, finding forest greenery for a Christmas wreath—there is familiarity to these daily, weekly, and yearly rituals that invite us to step outside the bustle of our lives for a moment and to remember our shared family ideal of loving one another the best we can.

When I was alone in the wilderness with the very real experience of feeling as though my life could be taken at any moment, ritual was all I had to rely on. I could not control what would happen out there, but I could bring rhythm to my time. In that rhythm, I discovered I could celebrate, create, and connect to what I love about being alive.

Ritual is my treasured reminder, with my children, family and friends, to pause time—to stop and notice what is unfolding around us. As we return to activities, stories, and places each day, each month, and each year, we can mark how we’ve changed, and how we are holding each other through those changes. We can celebrate for a moment that we are here together right now. Within our rituals, we acknowledge, “Look at what is happening right now. Look how we are able to love each other no matter what. Look at how bountiful is this earth and how precious our time together!”

Corianne Cayce will visit East West Bookshop to do a workshop called: TOWARD WHOLENESS: LESSONS FROM THE EDGAR CAYCE READINGS, BUDDHISM AND THE LATEST BRAIN RESEARCH on Oct 20.